Politics in Queanbeyan is finally nearing completion and in anticipation (and partly due to COVID) I am making all of Part One and a small section of Part Two available online for free by clicking here. (Posted July 2021, with updates to this page since).

Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander readers are advised that the paper contains names of Aboriginal people who have died.

It also contains references to terms and attitudes that may be inappropriate or insensitive today.

The completed work consists of three parts. –

Part One Prelude to Responsible Government – Dramatis Personae

Part Two 1856 to 1881 – Land, Religion, Roads and the Railway

Part Three 1885 to Federation – Parties, Protection and Federal Parliament

Part One covers the time prior to and leading up to the first elections held under responsible government in 1856. In this section there is a lot of dry material, facts and figures, a dramatis personae in more prosaic style, setting the scene for the more volatile history that follows.

Politics in Queanbeyan has been written from a broad perspective, the purpose being to bring character and life to elections and establish context to politics with specific reference to how it happened in Queanbeyan, the district from which was carved what was to become the Australian Capital Territory.

Essential data relating to all elections in the district can be found in the table here. (See details below). An introduction providing a general outline of the political history of the district is also found below.

Politics in Queanbeyan provides the background to the data, the real-life context behind the names and numbers and the street-level relevance of the debates, discussions, personal relationships, brawls and celebrations that shaped the laws and Acts that impact on our daily lives.

Please note that this is an extract from a lengthy work that covers the history of the district up to the establishment of the Federal Capital Territory and the national capital city of Canberra. It provides a preview into a work of several hundred pages. This excerpt consists of the pages as extracted from the book, minus the complete publication details, the complete work being as yet, unpublished. Abbreviations and References relevant to this extract are provided, reduced from the more extensive lists in the complete work.

Complete acknowledgments appear in the book but I am immensely grateful to Dr Helen K. Bones, Jonathon Auld and Ann Lyon, whose many hours in the NSW State Archives and Library, finding and digitising documents, was an essential contribution to the work. My thanks also go to staff at New South Wales State Archives and Records and the State Library of NSW, the heritage librarian at Queanbeyan, Ms Brigid Whitbred, Mr Alastair Crombie of the Hall and District Progress Association, my local Librarian, Ms Cheryl Elphick, and my local genealogical society.

Unless otherwise stated, most statements of land grants are derived from the Colonial Secretary’s Records Relating to Land, held by the NSW State Archives and Records (NRS 907), accessed from the Archives or via online databases on commercial websites.

Being on “Politics in Queanbeyan”, please note that, except where specified in the text, I intentionally have not focussed on geography. Where identification of original locations and place names is of issue, I have opted to quote official nomenclature as stated in the relevant and cited documents. For example, although there is some debate as to the precise location of the police station when established in January, 1838, I have referred to it as being “at the Junction of the Queanbeyan and Molonglo rivers”, denoted in quotation marks with a citation provided, it being directly quoted from the official designation as stated in parliament at the time.

Multiple names existed for individual locations at any time and place names were fluid throughout time. For example, distinct from the rugged Jingerras in the east, which formed a border with the County of St Vincent, the Tindera range south of Queanbeyan town was variously referred to Jindera, Tindery etc.

Further, general areas were often referred to by reference points such as nearby trig stations, geographical features, pre-existing native names or private stations, farms, selections and properties. Note that the invocation of such names in the text therefore does not imply anything other than the context indicated. For example, taken for a trig station at One Tree Hill, the term, “One Tree Hill”, could mean an inn that was erected nearby or to indicate the general locale around present day Hall, not necessarily implying the location of the trig station itself. Private property names were often taken from pre-existing unofficial references to general areas, such as “London Bridge”, a property south of Queanbeyan town, which also referred to both a specific natural rock feature and the general location associated with it.

Correlation with current locations is also difficult, as much of the original district no longer exists, but has been built over or is, as in the case of Canberra, now under Lake Burley Griffin. Modern suburb names, including in Canberra, do not necessarily correlate with historical locations.

Therefore, where problematic or unknown, I have intentionally not specified physical locations for certain places, but have referred to them in the context relevant to the concepts under discussion in the work. I have, however, made a point of including First Peoples place names and references where known.

N.B. On page 15, it should read “To the north were the Counties of King and Argyle and along the eastern border toward Sydney was the County of St Vincent, which contained the town of Braidwood and extended all the way to the coast at Bateman’s Bay. To the west lay the County of Cowley and what were to be the Counties of Beresford and Dampier lay to the south.”

To resolve geographical issues, the several maps below (please click on highlighted links) provide a general layout of the land over the years. All of the maps cited are held by the State Library of New South Wales. Specific locations of features and properties can also be determined by the many other maps and documents now accessible online.

Map of County of Murray, N.S.W. (1872) [held by the State Library of New South Wales]. Please note that this map needs to be rotated to show Lake George at the top to be facing North.

Bishop, G., & Lenthall Bros. (1872). Atlas of the settled counties of New South Wales [cartographic material] : This valuable series is complete in nineteen numbers, with the addition of a road and distance map of the entire colony : These maps have been compiled with great care from the latest government surveys; the mineral information has been obtained from the government survey and others; and the geographical and geological information from the works of the following authors, viz.: Wentworth, Lang, Hovel and Hume, Bennett, Mitchell, Wells, the Rev. W.B. Clarke and W. Wilkins. Sydney: Basch &.

Mitchell, Thomas & Davies, Benjamin Rees & Dixon, Robert & Mitchell, Thomas & T. & W. Boone (Firm). (1838). The south eastern portion of Australia showing the routes of the three expeditions and the surveyed territory. [Held by the State Library of New South Wales]

Cross, Joseph & Dixon, Robert & J. & C. Walker & Turtle & Ashton. (1846). This map of the colony of New South Wales exhibiting the situation and extent of the appropriated lands, including the counties, towns, village reserves &c.

Briand, George & Queanbeyan (N.S.W.). Council. (1862). Plan of Queanbeyan, County of Murray.

New South Wales. Department of Lands. (1904). Parish of Queanbeyan, County of Murray Land District of Queanbeyan, Gunning Shire, Eastern Division N.S.W.

Ms Sandra Young has also advised me of her excellent website on Queanbeyan military veterans and the Red Cross at australianmilitarymemorialsand

I am very grateful for the excellent feedback I have been receiving and extend my thanks to the curators of the Queanbeyan Museum, Ms Kerrie Ruth and Mr John McGlynn, the current editors of the Queanbeyan Historical Journal, Quinbean, information about which can be found here. Articles by myself have appeared in issues of Quinbean.

The material in this work has been thoroughly independently and originally researched.

Inadvertent errors aside, for which I apologise in advance, I can say that great effort has been made to ensure that the factual material in Politics in Queanbeyan – From the Counties to Federation is correct. Full references are provided, allowing for direct verification. Having done my own proof-reading I, of course, will be happy to know of any unintentional errors.

Please note that the construction of the whereabouts of the brig, “Bee”, was by myself, supporting Forrell’s contention that it may have been on that ship that Jane New sailed to Hawaii.

The work is copyright, so citation would be appreciated and formal reproduction will require permission, but otherwise the information is free to use for study and research purposes. You may download, print and share as you wish.

Please note that this research project has been entirely self-funded.

Joanna Davis, Northcliffe, Dec, 2022

N. B. Certain histories of the Queanbeyan district by previous writers contain errors which I have, to some extent, addressed in a paper kept at Queanbeyan City Library by heritage librarian, Brigid Whitbred, and which I have posted on this website at

The more comprehensive history covered in “Politics in Queanbeyan” will go a long way toward completing the more accurate depiction of this significant district and the pivotal figures who shaped its history. My work overturns much previously incorrect material and introduces much that has never been in the public domain before.

My research is original and independent and is based on primary documents and sources, on occasion double-checked by staff at relevant bodies, ensuring that, inadvertent errors aside, the material is accurate.

I realise that those who have endorsed, written Forewards to, presented, introduced, quoted, referenced etc., the incorrect work by previous writers were/are probably unaware that it was incorrect. My main focus is on getting the correct material into the public domain to correct injustices to individuals and so that meaningful analysis based on accurate information can take place.

I began this work as family history research, an innocuous project, I thought. I had no idea I would be revealing such important information in Australia’s history or uncovering some of its biggest “secrets”. It was not until after I had completed much of my own research that I even glanced at previous work on the topic, but, having completed much research independently, I was therefore in a position to recognise how incorrect certain previous work was, unlike many who would not have had that advantage.

Introduction

Even before there was Canberra, Queanbeyan was one of the most important electoral districts in New South Wales.

Consisting in turn of united Counties, then the Southern Boroughs and County Murray until the electorate of Queanbeyan was established in 1860, from 1843, the district was represented on the Legislative Council and then, with the establishment of responsible government in 1856, in New South Wales parliament, by some of the foremost people in Australian politics. These included Sir Terence Aubrey Murray, Minister for Lands and Public Works, later Speaker of the Legislative Assembly from 1860 and President of the Legislative Council from 1862, and William Forster, Premier, Colonial Secretary and later Minister for Lands. Murray and Forsters’ liberal politics spear-headed the introduction of reforms in New South Wales. Murray led campaigns for the abolition of the law of primogeniture and of capital punishment. Murray and Forsters’ support for National Schools and then Public Schools under Murray’s close friend, Sir Henry Parkes, was pivotal to their establishment. Nominated by Arthur Affleck on condition he introduce electoral reform, Forster put to the House his Electoral Reform Bill, the move that extended the franchise to all men over twenty-one without property restriction and introduced the secret ballot in New South Wales.

From the 1860s, the politics of the district was dominated by the battle for free selection, led by William Affleck, John James Wright, William Gregg O’Neill and John Gale, supported by the relatively reformist De Salis family in parliament, starting with the return of William Redman to support Sir John Robertson’s 1861 Land Bill, with its all-important Clause 13 – the “free selection before survey” clause. In 1869, William Forster was returned in an election led on his behalf by William Gregg O’Neill, who also successfully campaigned for Thomas Garrett of Shoalhaven and Daniel Egan of Monaro, when O’Neill was credited with almost single-handedly securing the Robertson Ministry in its battle against the “squattocracy” that had threatened to undo Robertson’s 1861 Land laws.

Local disputes over the roads and the railway spurred fierce in-fighting between the leading individuals of the district from 1864 until the Queanbeyan railway route was decided in 1881.

After the election of extreme protectionist, Edward William O’Sullivan, as Member for Queanbeyan from 1885, the battle between the “squatters” and free selectors was superseded by the war between free trade and protection, during which time the district was definitively politically and socially split in two. With aggressive strategising and local media support from the protectionist Queanbeyan Age newspaper, O’Sullivan held his seat for nineteen years against a procession of Free Trade and Labour candidates whose main aim prior to the introduction of income tax, was to introduce an equitable direct taxation system based on ability to pay and to abolish the protectionist’s sales taxes. import duties and tariffs that impacted hardest on the lower and middle income earners. Free trade principles also generally tended against the abominable closed borders policy of the protectionists which, in the form ferociously advocated by O’Sullivan and the Queanbeyan Age, translated into comprehensive race-based immigration restriction, come to be known as the ‘white Australia’ policy, with O’Sullivan claiming to have fathered its name.

While the Queanbeyan Age, under Gale family ownership until 1891 and then mainly Skelton Brothers and Cox until 1901, promulgated the conservative protectionism of O’Sullivan, John Allan “Jack” O’Neill’s Queanbeyan Times, established in 1879, embraced the principles of free trade/labour and gave rise to the careers of the liberally progressive John Farrell and Harry Holland, who were to go on to be leading figures in labour politics. Farrell helped found the Labour Party in Sydney and his colleague, future Prime Minister, Joseph Cook, became the first Labour representative in NSW parliament in 1891. Farrell was an advocate of Henry George’s land nationalisation principle and organised George’s visit to Australia in 1890. After an extensive career as a journalist, including as editor of the “Worker”, for which future Prime Minister, William Morris “Billy” Hughes, also wrote, Harry Holland established the Labour Party in New Zealand in 1917 and led it in Parliament until his death in 1933.

As the relationship between O’Sullivan and the workers’ movement descended into hostile enmity, under the new management of George Tompsitt, George B. Lillie, Edward Dornbusch and Arthur Ernest Kennedy from 1888 to 1892, the Times continued to support free trade, as did Jack O’Neill’s Queanbeyan Observer newspaper, established in 1889, until it was bought by John Gale’s son-in-law, Edward H. Fallick, in November, 1894, and came under John Gale’s management, at which point Gale turned its direction to protection.

Along with prominent free trade/labour advocate and colleague of Sir Henry Parkes, William Affleck, the more journalistically impartial Times and Observer newspapers, which brought balance to the Gale family monopoly on the media in Queanbeyan, supported liberal candidates against O’Sullivan, among them, the popular and technologically innovative, George Tompsitt, who introduced electricity to Queanbeyan at his wool-washing works and as Mayor in 1889, unsuccessfully attempted to introduce electric street lighting to the town against strong opposition, which included the Queanbeyan Age, at the time still led by John Gale, and by John Gale at the Queanbeyan Council.

With the folding of the Times in 1892 and O’Neill’s sale of the Observer in 1894, there was no longer a voice in the local media for free trade/labour, but in 1894, locally-based William Affleck was elected as Free Trade Member for Yass, in Government for five years with George Houston Reid and alongside his friend, Labour leader, William Morris “Billy” Hughes, while Sydney-based Member for Queanbeyan, O’Sullivan, and the Protectionists were in opposition. From 1899, Affleck, still Member for Yass, was then in opposition until 1904, while O’Sullivan became Minister for Works under the Lyne Government in 1899. The introduction of the Land and Income Tax Assessment Act in New South Wales in 1895, under the Reid Free Trade Government with the support of the emerging Labour Party under McGowan and Hughes, rendered the fiscal battle between free trade and protection obsolete. From then on, the main local political focus was on Federation, followed by the establishment of the Federal Capital Territory and the selection of Canberra as the site for the nation’s capital, with Federal parliament transferring from Melbourne in 1927.

Against strong opposition, Queanbeyan remained conservative until in 1904, both the Observer and the Age, the latter also back in Gale family hands from 1901, turned on O’Sullivan, who severed his connection with the district and stood for Belmore in Sydney, while local candidate, Dr. Patrick Blackall, was defeated by the Liberal Reform Candidate, Allan J. Millard. From 1906 to 1910, Granville De Laune Ryrie led the electorate as a Liberal until J. J. Cusack then secured the district for Labour.

The last election for the division of Queanbeyan was held in 1910. With the establishment of the Federal Capital Territory, Queanbeyan lost much of its electorate to the new Territory. For the NSW general election of 1913, a major redistribution saw what was left of Queanbeyan absorbed into the district of Monaro.

Politics in Queanbeyan – From the Counties to Federation captures some of the energy and character of one of the most significant and politically active districts in New South Wales. The book, with its broader coverage and detailed portraits of individuals and events and how they shaped politics, will be available in the very near future.

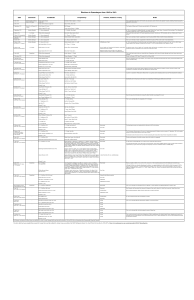

In the meantime the poster-sized table below summarises the essential stats for all elections in the district from 1843 until 1910 when the Queanbeyan electorate was abolished on the formation of the Federal Capital Territory. The table has been compiled from original research by Joanna Davis and information from the New South Wales parliamentary website, New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007.

(Please click on the table and zoom to display full-size)

New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007 is an invaluable archive of information on historical elections in New South Wales and a major feat of research. Due to a fire and other reasons, the original records relating to NSW elections was lost in the 1890s. The only source of information is the local newspapers of the time, which fortunately were prolific and covered all polls in detail. The only way for any details as to dates, candidates, parties and results could be ascertained was by trawling through every available newspaper in NSW, which Antony Green has done with outstanding accuracy. The collation of that information makes the resulting website an essential database in Australian political history. The data relating to Queanbeyan is verified by my own original research on that topic.