Located among the tall jarrah, marri and karri forests in Western Australia, Joanna Davis Publishing is the main publishing platform for my work, writing as Joanna Davis. Publishing across diverse genres, media and formats, it is the portal for many exciting projects to come, including work of significant national historical interest.

Joanna Davis

In brief –

Born: Bathurst, New South Wales, 1961

School: Kelso Public, Cooke Point Primary, Hedland Senior High School

Tertiary education: Juris Doctor; B.Sc., Grad. Dip. Ed., part-completed Masters in Astronomy, British Qualified Teaching Status, units in Archaeology.

Also teach French.

Religion: None, atheist

Politics: Centre-left. Confirmed “leftie” and ardent environmentalist. Voted Labor all my life or Greens if no Labor candidate. Voted for a Republic in the 1999 referendum, “Yes” to same-sex marriage in 2017 and “Yes” for “The Voice” in 2020.

Like Elizabeth I, never married, no children, but have a terrific brother and nieces, nephews and great nieces and nephews all of whom I adore!

Don’t smoke, don’t do drugs, do like an occasional glass of red and dark chocolate (I’m just going with the science on this – if you choose the right study, you’ll find they’re practically health foods!)

My research in Australian history has resulted in several works in fields little covered previously and some exciting discoveries.

I have written some entries and/or supplied some material for the biographies of former members of NSW Parliament, which appear on the Former Members page of the NSW Parliamentary website, the home page for which is here.

I was honoured to be among those invited to provide input into the new NSW Parliament House website covering politics in New South Wales prior to responsible government in 1856, the home page for which is here.

My studies have encompassed a diverse range of fields, including astronomy, ecology, atmospheric science, anthropology, historical archaeology, energy studies, geography, social and economic policy, energy policy, science and technology policy, library studies, sustainability studies/technologies, history and philosophy of science and science fiction.

While studying, I worked in several positions in New South Wales and Western Australia, including briefly for the WA Police, and I briefly taught secondary school science in WA before from 2004 I taught Physics and Science in England for several years.

I narrated audio books for Narkaling, who produced recordings in altered speeds for people learning English as a second language or with reading difficulties (links below).

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/8167197

https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/8167866

I have lived in Northcliffe, WA, since my return to Australia in 2009, on the property my brother and I inherited from our father in 1997.

I believe strongly in communicating science to the public and along with my previous teaching and books in progress in the field, I have delivered astronomy nights in WA, which have been a great success and enormous fun.

More information as to my ethos and thoughts on any events can be found in the “Posts” on this site.

The wordier account –

Through my mother, I am directly descended from four pioneering families of the Queanbeyan district – or what is now Queanbeyan, Canberra and the ACT – the Afflecks, the O’Neills, the Boltons and the Griffiths’.

My great-great grandfather, James O’Neill (son of Irish police officer, John O’Neill, and Ann Townsend), emigrated to Queanbeyan from Co. Sligo, Ireland, in 1854, joining his brother, William Gregg O’Neill, the Chief Constable of the Queanbeyan police district. [According to their uncle, Dr William O’Neill, chief medico in Lincoln, physician to the Lincoln Lunatic Asylum and noted amateur archaeologist, the O’Neills were directly descended from Hugh O’Neill and therefore, “The O’Neill”. No idea if it’s true or not, but I believe it and expect to be treated accordingly! More info is on Dr O’Neill’s plaque in Lincoln Cathedral and in The O’Neills of Queanbeyan.] In 1859, James married Mary Ann Affleck (daughter of Edinburgh book-seller and printer, Arthur Affleck, and Ann Skinner Wishart, whose family ran the grocers in Kinsgbarns for generations. Arthur and Ann ran a grocers at Wemyss. Fifeshire, before sailing to Australia with their two children, William and Ann, arriving in 1855. James began a saddlery and harness-making business in Trinculo Place, Queanbeyan, in 1855. He ran the Royal Mail to the Snowy Mountains from Queanbeyan from 1856 and he and Mary Ann ran the longest running family-owned Royal Mail and coaching business in Queanbeyan, still operated by their sons well into the twentieth century. The heritage-listed cottage James and Mary Ann lived in for some time in the 1880s still stands in Trinculo Place as home to the Queanbeyan Arts Society.

In 1858, my great-great-great grandfather, Arthur Affleck, nominated William Forster to NSW parliament as Member for Queanbeyan on condition that he put his Electoral Reform Bill to the House, the Bill that saw the franchise extended to all men over twenty-one without property restrictions and introduced the secret ballot in NSW. With liberal principles, including support for womens’ rights, and considered a principled and brilliant analyst, he was a major figure in Queanbeyan politics for three decades.

Arthur’s and Ann’s son, William Affleck, a leader of the free trade/labour movement from the 1860s, was an adviser to Free Trade leader, Sir Henry Parkes, and, entering parliament as Member for Yass in 1894, was a major driving force in the introduction of George Houston Reid’s Land and Income Tax Assessment Act in 1895, when for the first time people in NSW were taxed according to wealth, as opposed to the system of indirect taxation in the form of regressive sales taxes and import duties advocated by the Protectionist party. Alongside Louisa Lawson, mother of the poet Henry, William helped lead the womens’ movement and forthright, principled and independently-minded, as noted by his friend Prime Minister, “Billy” Hughes, who devoted an entire section to him in his book, Policies and Potentates, was considered the voice of conscience in the NSW House during his ten year term in Parliament. He was also the main force behind the selection of Yass-Canberra as the location for the Federal Capital Territory.

My great-great uncle, WiIliam Gregg O’Neill, was Chief Constable of Queanbeyan from 1853 and a leading man of the district, establishing schools and churches and the general social life of the district until in 1862 he was promoted to Sub-Inspector and then placed in charge of the Gundagai sub-district. He was famously involved in a shoot-out with bushranger Ben Hall’s gang at Jugiong in 1864 before leaving the police in 1866 and returning to Queanbeyan, where he was a central figure of the district, maintaining schools, churches and the Mechanics Institute, as Secretary and then President of the Hospital and successfully leading the movement for municipalisation, while refusing to stand for office himself, saying men of his temperament were not suitable for positions where diplomacy was required!

In 1879, James and William Greggs’ brother, John Allan O’Neill, founded the Queanbeyan Times newspaper, a profoundly significant publishing venture which was to give rise to the careers of such figures as poet, journalist, founding member of the Labor Party and a main force behind Henry George’s 1891 tour, John Farrell, founder and Leader of the Labour Party in New Zealand, Harry Holland, and the man considered by his best friends, John Farrell and Henry Lawson, as Australia’s greatest poet, Victor James Daley.

Although W. G. O’Neill, the Afflecks, the town’s first Mayor, J. J. Wright, and John Gale, who founded the Queanbeyan Age newspaper in 1860, were a close-knit oligarchy who founded and led the Queanbeyan district for over thirty years, politically, as left-wing progressives, the O’Neills and the Afflecks were opposed to the conservative right-wing protectionist politics of Wright and Gale. From 1885, when the district was definitively split in two by the war between Free Trade/Labour and Protection, along with such figures as George Tompsitt, the O’Neills and the Afflecks supported Free Trade/Labour campaigns against John Gale’s man in parliament, the Protectionist Member for Queanbeyan, Edward William O’Sullivan.

My other great-great-grand parents via my maternal grandmother, Joseph Bolton and Mary Ann Griffiths, married in Queanbeyan in 1865. Joseph, originally a brickmaker and stone mason from Worcestershire, had arrived in Sydney as a free settler in 1854. His brother, George, had been in the district since the 1830s, initially on John Hosking’s “Foxlowe” estate, probably as a convict. Mary Ann, hailing from Walton-on-the-Hill, Ulvertsone, and Duke Street, Liverpool, had arrived with her free settler family as a one-year old in 1848. After leading a career said to read like a fiction thriller, including bringing the landmark Hetherington murder case, Joseph and Mary Ann’s eldest son, Inspector Harry Bolton, was head of the NSW Mounted Police and the Police Training Depot in Sydney, whose last act before his retirement in 1927 was to lead the mounted escort for the opening of federal parliament in its new home in Canberra. [More information about Joseph and Mary and their son, Harry, can be found in The Boltons Of Ginninderra.]

Through my maternal grand-father, I am descended from the Davis’ of Parkes. My six times grandmother, Margaret Fitzgerald, was born in Sydney in 1833, her father having arrived in New South Wales as a convict fourteen years earlier. They lived in Bathurst, Forbes and Parkes. [Note this family is unrelated to the Davis’ of Ginninderra, Queanbeyan.]

In the 1950s my parents met when living in the same street in Bathurst – my mother, Jeanette’s, family in the country since at least 1819 and my father’s family, “new Australians”, as they were called back then, war refugees who had emigrated in 1950.

Living within the brilliant historicism of Bathurst, on the Macquarie River, just upstream from Governor Macquarie’s old place, in a fabulous falling-down old house that I think was built around the same time, we were surrounded by history and what we didn’t live in we had ingrained into us at school (even if it was the sanitised version we all now know to be somewhat unreliable). Bathurst was also home to Lieutenant-Governor William Stewart, who provided Bathurst with its very own “castle”, an important contribution to childhood imaginations.

My maternal grandparents, Leslie Patrick Freeman Drummond Davis and Doris O’Neill, were model working-class Australians with good values and a passion for Australian history. Born in Forbes in 1909, my grandfather was a railway charge-man, marrying my grandmother in Parkes, where my mother was born, after which his job took the family to Narranderra and Junee, before they settled in Bathurst. My grandmother was born in Macksville, New South Wales, in 1910 and helped her parents, Robert and Annie [née Bolton] O’Neill, both born in Queanbeyan, manage hotels they owned and leased in the Macleay River/Kempsey district, Sydney and Parkes, including the “Flagstaff” hotel in Princes Street in the Rocks, Sydney, which was torn down to make way for the Harbour Bridge. Doris’ sister, Alice, was one of the first female Assistant Town Clerks in NSW, when appointed in Kempsey. My grandmother taught me my first notes on the piano that had belonged to my great-grandmother, Annie, and took me to the local Eisteddfods and “Fantasia” at the local cinema. My grandfather had been a rugby league coach and every Sunday, Nan and Pa took my brother and I to the local match in their big, old Humber, when we would picnic on thermos tea, sandwiches and Strawberry Mallow biscuits. [Like modern Iced Vo-Vos but with puffy marshmallow and more jam. The clarification is needed as a bit of a debate is going on, with some claiming “Iced Vo-Vos never had marshmallow” but always had fondant, as per the current version. Don’t know about that, but a company definitely made a puffy, marshmallow version, albeit with a different name. It’s no longer available , so the modern “Iced Vo-Vo” is the closest in form to give an idea, even if by a different company. There is a version still available in Britain. J]

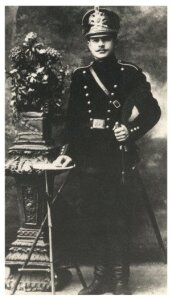

My grandparents on my father’s side, Jan Tatarynowicz and Sophia Voynich, were people of progressive values with an amazing history from the “old world”. From direct descendance from Ghengis Khan to giving away estates in Russia by choice prior to 1917, while also being an anti-soviet Tsar loyalist, for which some of his family fled to China and others died in a gulag, emerging from two World Wars and a revolution with strength and compassion, ruled by my Polish peasant grandmother, my grandfather’s sense of civic duty extended into Australia.

Originally a lawyer and Police Chief, my grandfather had fled to Poland, where he was a member of the Democratic Socialists Party and he, my grandmother and their children, including my father, born not long before Poland was invaded, spent most of WWII in a labour camp at Karnap-Essen, after which they were “displaced persons” in Munich before sailing to Australia from Naples, Italy, in January, 1950, on the “Queen Nellie” as refugees. They initially lived in the migrant camp in Bathurst but soon the whole family were part of the wider community in Bathurst and Sydney. In Bathurst, my grandmother worked in a clothing factory and my grandfather taught my father about horses, they then partnering as legends in the local harness-racing scene. As my grandfather’s immigration officer wrote, “His lack of English has not been any detriment to his successful handling of horses in one of the toughest ‘Sports’ in Australia” and nor did it prevent him from taking part in local Municipal elections. [N.B. Not an endorsement of gambling or racing. My father and grandfather were legends of horse-care. My father was a blacksmith and custom-shod for many. They would be horrified at the recent revelations about the horse-racing industry and the turn that racing has taken into corporatised, inhumane ‘gambling’. They always treated their horses as part of the family and kept them at home post-racing or ensured they were well-kept with trustworthy neighbours. Back then, for them, it wasn’t about money. My thoughts on it here. J]

My uncle, Phil Davis, my mother’s brother, who made his start in journalism on the local Bathurst paper, the Western Advocate, worked as a leading crime reporter on Sydney papers. He broke the Bogle-Chandler story (a photo of Phil and a police officer at the Chandler house can be found here (Getty Images, Fairfax Media Archives) and covered the Graeme Thorne kidnapping case.

Following the great Labour Prime Minister, John Curtin, from 1949, Australia was under entrenched ‘conservative’ government for twenty years under Robert Menzies, followed by several insipid leaders, the culmination of which was William McMahon in 1971. Fittingly, as the leading crime reporter for the Sydney papers, by 1968, Phil was called to Canberra to work for the government. Initially, he worked with Phil Lynch, Minister for the Army, at the time. Phil, my uncle, was a member of the Labor Party, but he saw it as his job to work as an impartial journalist, believing the government should be communicating better with the public. Unlike then Prime Minister, John Gorton, almost Labor man, Phillip Lynch was opposed to the “white Australia policy”. By 1970, Lynch had become Minister for Immigration and in August, he, Mrs Lynch and my uncle toured continental Europe, England, Scotland and Ireland in a major immigration drive, a semi-revival of the Labour Party’s post-war initiative, following Australia’s very restrictive immigration policy that had been in place since Federation. It was a successful tour that helped progress Australia out of its parochialism and Phil being married to an immigrant family through his sister provided valuable insight. One improvement was the building of housing within towns and cities for more immediately inclusive integration, instead of placing people in migrant camps, as had previously been the case.

Mr and Mrs Lynch at No. 10; Paris, Rome with Pope Paul VI, Rome (1), Rome (2), Athens, Edinburgh, London, Dublin, Geneva, Frankfurt and Bonn, when it was the capital of West Germany prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall; discussing migrant housing in Melbourne in a progression from the migrant camps of the 1950s.

Above photos from the programme are held by the National Archives of Australia (A12111, 1/1970/25/). I’ve identified Phil appearing in all these photographs of the tour, except the first of Mr Lynch at No 10, as he’s not in that one.

As was the “white Australia policy”, the Vietnam War also, was an abomination and an allegation of water-boarding by the Australian Army was one of the reasons Phil, my uncle, was originally called to Canberra to work for Lynch when Minister for the Army. Lynch called for an inquiry into the allegation, supported by Gough Whitlam. However, Prime Minister Gorton refused. My uncle, Phil, believed in open and consultative government. He introduced the first daily press briefings from Parliament House and created the role of political advisor.

During this time I was a super-student at my local public primary school in the city which was also home to several private boarding schools, including Scots College, where my mother worked in the kitchen.

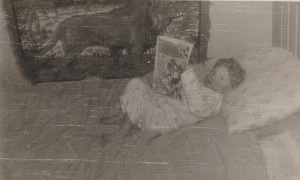

It was an exciting time. I had chicken pox in July, 1969, so I got to watch the moon landing at home. I also got to see “Animal Farm” on TV, immediately understanding its statement against totalitarianism. An excellent book prize, from around then was “Anna and the Snowdrops” by Jane Kozo Kakimoto Carruth. Of the writers my mother and grandmother brought me up on, Louisa May Alcott’s “Little Women” made a great impression. On TV and at the movies, Jules Verne, “Namu, the Killer Whale”, “Dr Who”, “Star Trek”, “Gulliver’s Travels”, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and “Micro Ventures” from the “Banana Splits” all made sense to the budding scientist/adventurer, who, from early times was going to be a writer, space scientist, marine biologist and environmentalist, even if cybermen terrified me.

After giving up harness racing on Mum’s orders, with his father-in-law’s help, Dad became a train driver with the NSW Government Railways, including doing the Bathurst to Sydney run. This was a fortuitous career path, as in 1971, we drove to Port Hedland, in Western Australia, where Dad drove trains for one of the local mining companies – being from Ben Chifley’s Bathurst and a Labor ‘true believer’, what else?

During a previous Christmas vacation, we had driven a big old sky blue Kombie van through Dimboola, Renmark and Mildura to Melbourne and the furthest known reaches of civilisation at the time, Adelaide. A schoolmate had also recently migrated to South Australia and we had all been excited at that. To go to Western Australia was, well, where was that, exactly? As our teacher pointed to it on the map, all we saw was a great blank space that took up a third of the continent with a bare note that Dirk Hartog had landed there in 1616 and apparently nothing much else had happened there since.

By August, we had loaded up our green Holden, “Betsy”, strapping the big old iron railway trunk that had also belonged to my great-grandmother, Annie Bolton O’Neill, on top, and ventured into the great unknown. Called in on Phil in Canberra and then the “Narranderra Davis’ ” (Mum’s other brother’s family), from where we put the trunk on a train and set off across the Nullabor, still dirt at the time, heading for Perth and then the northwest.

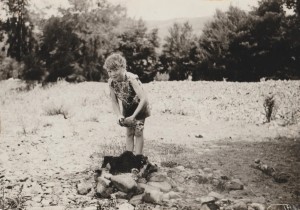

As we drove into Port Hedland and our house overlooking the beach, expecting to see sailing ships and buccaneers, we instead instantly stepped from colonial Bathurst into the twenty-third century as the mining boom was modernising the country and we found ourselves living in a futuristic world surrounded by pristine azure-blue ocean and rust-red desert, in the setting from a science fiction movie that was the north of the ’70s.

The joint venture iron ore mining company Dad worked for was far-sighted and looking for long-term employees. As encouragement, they provided good quality, cyclone-proof family housing, paid the air-con bill and provided any plants for greening the gardens as required, sensibly, even Australian plants suitable for the local environment. My father was a local union advocate and within his broad principles of racial and gender equality led, among others, one of the first wrongful dismissal cases for a female employee. As due to the original long-term planning, mining in the north is still a mainstay of the Australian economy, I don’t think many people in the “Eastern States” would think of WA as a blank space on the map anymore!

Within a unique spirit of egalitarian diversity, the Pilbara was an exciting place in which to grow up. Although there were some locals, black and white, almost everyone came from somewhere else, both from Australia and around the world, so our world was a mix of people from all racial, religious and cultural backgrounds, equalised by a shared standard of living provided for, directly or indirectly, by the, then, community-minded mining company. There were issues, certainly, but it came so near to an idyll, most could concentrate on accomplishments higher than survival, with all the more incentive to fight the good fight for all people to know the same. One of the biggest issues was the inexcusable treatment of First Nations people, an experience that has formed a major basis of my sense of social justice.

Although baptised a Catholic, I was always an atheist. I made my Communion when a child in Bathurst, because that’s what people did (although he too was not religious, my uncle, Phil, gave me rosary beads blessed by the Pope for the purpose during his 1970 immigration tour of Britain and Europe), but a couple of years later, I made a conscious decision not to make my Confirmation. Although my mother had bad memories of having her knuckles beaten while playing the piano, thus ending her interest in it, despite my father’s efforts to encourage her, there was no mistreatment of myself by anyone. Nuns had taken good care of me when I was in hospital when I was two and in an instance of an (unsuccessful) attempt on my person some years later, it was good, genuinely Christian and devoted members of the Church who acted on it. The Sister who took us for Scripture in Kelso, Bathurst (when they still did that for an hour a week in public schools and which, fortunately, they do not still do), was a genuinely kind, wise lady. The priest who led school scripture in Hedland, when we went there when I was still in primary school, was a good man, who taught of the “guts” it took to stand up to evils like apartheid. For my grandparents on both sides, their religion had provided internal strength against real evils and hardships they had seen during, on one side, two world wars and a revolution, and on the other, two world wars and the 1930s depression. When I made my Communion on 10 August, 1970, my grandmother on Dad’s side gave me a Star of David, a powerful message from a woman who spent three years in a labour camp during the Second World War. [Back when a Star of David was a symbol against oppression, not one causing it, as in Gaza and the West Bank now. They taught that “never again” meant “never again for anyone”.] That being said, my parents and grandparents were not “religious” as such, but scientifically atheist. Apart from midnight mass at Christmas, we almost never went to Church or attended to all the rituals. In fact, my grandparents were very worldly and detested high-minded hypocrisy. For them, religion, in principle, was the difference between humanity and “living like animals”. They didn’t believe in a man-like figure or consciousness controlling everything, only that we all answer to principles outside of self-interest. They believed in evolution and all things scientific. By religion, they meant a set of principles by which we prevent the moral descent of man into “Lord of the Flies”. All noble and good, excepting that for my atheist lawyer grandfather and atheist Labor supporter and union advocate father, who believed religion to be “the cause of all wars”, the law was more important than religion in preserving and enacting ethics. Among his many trades, my father was a watchmaker and, along with himself, personally, at times having to fix the trains he drove in the Pilbara desert, he knew only too well the mechanics of motion.

Apart from myself equally considering religion to be largely irrelevant to prevention of society’s descent into degradation, or, if anything, often being responsible for it, my decision not to make my Confirmation was entirely intellectual and one I made with deep consideration. I believed in science and the first Confirmation lesson with somewhat less knowledgeable people was enough to fill me with dread. Having standard Biblical text hollowly and superficially recited to me in, essentially, nothing more than tooth-fairy magic interpretations or misreadings, felt childish. Things thrown at us with expectation of unquestioning subservience, even if it was clearly impossible, felt really, well, stupid, and I felt like I was being forced to give myself to a swamp creature, something from the primordial slime. I knew these were the “kiddie” versions, which my intellect far exceeded, but even the more advanced philosophical grounds did not explain the universe as science did and merely verified organised religion as being manipuated and manpulative. A pivotal question on my mind was that of suffering. Why would a supposedly benevolent God allow so much suffering in the world? Or more, precisely, cruelty. God was just sitting, watching, while bad things happened? Then what purpose did God serve? The Church’s answers, simplified or sophisticated, did not make sense and the more convoluted the answers, the less sense they made. If God made man in his image, an intentionally cruel God was not one I could like or relate to. Science’s answer is unequivocal. It is a null question. The question does not exist. There is no external entity, anthropomorphic or otherwise, directing that cruelty exist. The reality is that people cause suffering to others, not God, and the alleviation of it does not lay in mindless acceptance of its necessity. Importantly, also, there were the clashes with known science. God, who supposedly knows everything, doesn’t know about evolution? Or of any of the true mechanisms by which the universe works, which is what was of interest to me. The other superstitious claptrap was just embarrassing. My allegiance was to truth and if the Church and truth parted company, I knew where my honesty lay. I therefore made a conscious decision that I could not swear myself to something I did not believe in. In delaying my departure past the first “lesson”, I had really only been thinking of what Mum would think, but by the end of the second, I couldn’t bear it and I told her I was not making my Confirmation. “Ok”, she said, actually relieved, and that was that. For her, having been pregnant with me when she was married, it meant one less finger being pointed at her in the name of “the Church!”

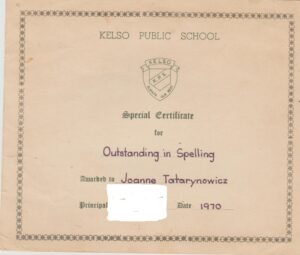

I was top student in primary school, winning several awards and when I complained we didn’t have any science, some science lessons were introduced. I continued to excel in high school and was fortunate to have encouraging science and literature teachers and as a Principal, Barry Cohen, who co-authored “Twentieth Century Australia” with historian, David Black, and who encouraged me in my history studies. I learned scuba diving at a school summer camp near Rockingham, outside Perth, in the days I was also going to be a marine biologist.

After the move to Hedland, we still spent occasional Christmases in Bathurst and Sydney and, escaping Bathurst winters, my grandparents, Doris and Les, stayed with us in Hedland for several months at a time. Doris sent us the Bathurst papers every week and I was kept up to date with all happenings in Sydney through my uncle, Phil, and regular correspondence with a cousin (great lady, Assoc Prof at Uni of NSW) and in London with a best friend since primary school in Hedland, who moved to England and went to LSE.

I was on a Girl Guide excursion on Pippingarra station during Gough Whitlam’s 1972 Labor election win, when listening to it on the radio, my friends and I celebrated that “the Revolution” had come, unfortunately followed by the opposite kind of revolution a few years later.

In 1978, I was disturbed by the Newfoundland seal cull and I performed my first deed as an environmental activist by placing a poster about it in the local phone booth. Unfortunately, the other side of the page had a picture of near-naked dancing girls on it, which showed through the transparency of the glass, so I quickly took it down before I got arrested, not for being an “activist”, but for fear of an indecency charge (an early recognition of how politics works). However, watching a forest protest on TV, my father made a comment that stuck. “Look at them!”, he said, of people hanging from trees and chaining themselves to bulldozers. “Who’s going to listen to them? They have a point, so why don’t they form a party and sway the electorate. That’s what democracy is for.” A few years later, the Greens formed around the world and look at them now! I recognised very early that attempts to save the environment would never gain respectability without science and it frustrates me deeply that the planet is still at the mercy of anti-science advocates.

Throughout my high school years I was still constantly ahead, so usually top in English, Science, French and History, I think they stopped having the awards.

By the time I was in Yr 11, I was doing Yr 12 English and the school considered I should go to university a year early, but that didn’t eventuate, so after tutoring some lessons, I had a term and a bit off before doing my Yr 12 exams, during which time I worked voluntarily as a teacher’s aide at my former primary school and began writing intensively. A novel about white and first peoples’ experiences in the north-west I have stopped and started many times and a lighter work I began researching at the time, an adventure novel with a message, “Katajarri”, I only just completed a few years ago!

I refused to be forced to divide myself between science and the humanities, so I decided to specialise in humanities at school (English, English Literature, History and Economics) with Biology and Human Biology, before studying science at university. Along with my love of physics and astronomy, aided by the dazzling Pilbara skies, pivotal intellectual experiences for me were understanding the mechanisms of DNA and exploring the micro and macro worlds beyond immediate experience. Literarily, I noticed Shakespeare, Marlowe and Thomas Hardy, while Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying” demonstrated the universality of the human experience beneath our often ridiculous surfaces, Patrick White’s “Voss” impressed with its incisive imagery and Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” made great contemporary literature excitingly and immediately relevant. Augmented by “100 Great Science Fiction Short Short Stories”, Homer’s “Odyssey” has remained by my bedside for all time.

During that time I decided to solve the world’s energy crisis. As part of this modest endeavour I dragged friends into “assisting” me in experiments measuring the energy content in blades of spinifex. This was superseded by an intention to make a fortune writing anonymously so I could solve the energy crisis by funding nuclear fusion research (not to be confused with nuclear fission, which is a very different matter, and now superseded by solar and wind for efficiency and reliability). As with that, my attempts to solve world hunger and save the environment are also still works in progress (the old joke that fusion is “always fifty years away” is as true now as it was – eighty years ago).

One of the advantages of growing up in the northwest, where, initially, there was no commercial television or radio and only the ABC at the time, was the freedom from the influence of social stereotypes, allowing me to excel as an uncompromisingly intelligent woman without any self-consciousness of the fact that I was doing that. However, while I recognised and loved the unique greatness of the northwest, like most young people, thinking I lived far away from where “real life” happened, I couldn’t wait to get to “civilisation”, where all everyone did all day was discuss ancient Greece, “Hamlet”, Galileo and Isaac Newton. Kafka’s dairies echoed, in reverse, my experience of life in a cultural desert. However, unlike Kafka or Thomas Hardy, I wasn’t miserable enough to be a great writer yet, so I put my more literary mind aside to study science.

When I flew into Sydney in December, 1979, to start a B.Sc. at university, my main goals were the same as that of most teenagers – to get copies of the BBC’s “The Voyage of Charles Darwin”, “Microbes and Men” and Shakespeare’s plays, to roam the halls of the State Library and to join Greenpeace.

I studied science at uni, during which time I was on the Biological Society Committee and Secretary of the Astronomical Society, while also becoming a writer and “doing” music.

I was an inner city person, enjoying the academic life in historic Annandale, going to uni or to work at a lab or in the city, being able to spontaneously race down to the Opera House to hear even just a single Act or Movement I liked, thanks to student rush, under $10 at the time, having the privilege of being able to hear some of the greatest musicians in the world. That interest led to me being elected a Director of the Music Broadcasting Society of NSW and programme planner, producer, programme writer and announcer at its classical music radio station, 2MBS-FM, glad to support emerging Australian music and musicians during a time that, heading toward the1988 Bicentennial and unshackling itself from the colonial yoke, Australia was trying to ‘find itself’. The First Peoples had known where it was all along, of course, and I protested at the lack of diversity in the classical music scene during a time that, with one notable exception, there were no black or Asian faces on the Australian Opera stage or in the orchestras.

The ‘70s and ‘80s was a time of great Australian TV and movie productions as Australia was enjoying a re-emerging sense of its own identity and history. “The Getting of Wisdom” stands out for me and I’ll never forget seeing the poignantly beautiful “We of the Never-Never” in 1982, when for the first and only time in my personal experience, an ordinary Australian audience at an ordinary screening at a cinema in George St, Sydney, broke into spontaneous applause for a movie.

The wee hours were for writing, usually in front of the fire with a glass of red or stargazing through my tiny backyard telescope or with astronomical societies.

My uncle, Phil, did not particularly like working with McMahon, who had since become Prime Minister, and after the 1972 election, he broke to McMahon how disliked he was and advised him not to run again. [You’re welcome, Australia!] Although Gough asked him to work for him, Phil was glad to “get away from the skull-duggery of Canberra” and to partner with Mike Willesee as his Executive Producer, bringing high-quality news and current affairs to the broader Australian public, previously the sole domain of the ABC. Phil was EP for Mike in an exceptional blood-brother partnership for many years, starting with “A Current Affair” on Channel 9 and then “Willesee at 7”, “Willesee ’80” and “Willesee ’81” on Channel 7. When Mike then returned to Channel 9, Phil stayed at Channel 7 and introduced “Terry Willesee Tonight”, which became “TWT”. Phil became head of News and Current Affairs at Channel 7, then still owned by Fairfax, during a high-octane time during which he enjoyed a reputation as one of the most respected journalists in the business. He introduced “Newsworld” with Clive Robertson and new formats for news presentation. Disagreements between Phil and new station-owner, Christopher Skase, ended with Phil leaving Channel 7 in August, 1988, after which he ran a corporate video business. The Sydney Morning Herald’s obituary on Phil’s death in January, 2016, can be found here. [N.B. Between Jenny Cope and Carol Summerhayes (Gough Whitlam’s personal assistant), Phil’s partner of several years was former model, Judy, who seems to have been accidentally omitted from his obit. Also, it may read incorrectly in referring to those surviving him being his wife, his nieces and nephews and “all those children”. It should say “God-children” as Phil had no children of his own]. With Carol Summerhayes, formerly Gough Whitlam and Governor-General Deanes’ personal PA, Phil supported his friend, Labor speech-writer, Graham Freudenburg, in writing his book, “Churchill and Australia” (ebook available here). [I can’t help noticing how standards in television news and current affairs have gone down since the departure of people like Phil, Mike and several other standard-setters of the time.]

The ’80s was a promising time. Along with Australian achievements, from all sides, intelligent people were laying the foundations of an intelligent world unimpeded by the stupidity of the Cold War. “Oppenheimer”, “Reilly, Ace of Spies”, “Rumpole of the Bailey”, “Brideshead”, everything by Sir David Attenborough and Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan and Steven Soters’ “Cosmos” are probably still the stand-out TV series’ of the early ’80s for me, among many excellent productions from that time.

Alongside science studies, I kept up my literariness, among extensive reading, revelling in Samuel Johnson’s History of Rasselas, more Shakespeare and Thomas Hardy, lots of poetry and lots of science fiction. Karel Capek’s stories were interesting. He gave us the word, “robot”, from “Rossum’s Universal Robots”. I note that forced labourers during WWII were called “robotniks”, which I found startling when I saw it on one of my grandfather’s immigration forms.

I excelled at tertiary studies, however, I don’t mind admitting that due to several external “misadventures”, it took me a long time to complete my undergraduate B.Sc. between starting it in Sydney and completing it in WA. Fortunately, my parents, brother and many generous uncles, aunts, cousins and friends were able to help me through hard times. I then made up for lost time by doubling up on post-grads, while working full-time and writing. To friends, family and all those supportive during extraordinary circumstances, I am sincerely grateful and appreciative.

Some of my work, fiction and non-fiction, is now available, while more will be in the near future, including a book about a Renaissance lady pirate-captain set on the eve of the enlightenment.

From my grandparents I gained much valuable information which has led to major discoveries in Australian history that are covered in my books and articles currently available and those to come.

Among other things, I have worked in several laboratories in NSW (from 1985 to mid-1986 at the NSW Gvt testing Laboratories in Glebe, then clerical work for a private pathology lab and then the NSW Gvt engineering lab), for the NSW Attorney-General’s Dept, at the WA Commercial Tribunal, briefly for the WA Police and then I briefly taught secondary school science in WA before from 2004 I taught Physics and Science in England for several years, attained my British Qualified Teaching Status (via my school, OfSTED and the University of Hertfordshire), completed units in archaeology at the University of Leicester and attended a short field course at Kent Archaeological Field School.

Universities I have attended (on-campus, on-line or by distance) include the University of Sydney, Edith Cowan University, Murdoch University, University of Western Australia, University of Western Sydney, James Cook University and the University of Leicester. As part of my wannabee astronaut preparation I did the Private Pilots License theory at Sydney TAFE – Basic Aeronautical Knowledge (back in the days it was still called that) and Air Navigation. Couldn’t afford the practical flying lessons, so that’s where my astronaut aspirations went!

My first time out of Australia was in January and February, 1992, when I was in Britain, Italy, Switzerland and Austria. Since 2004, I’ve also travelled in Britain, Italy, France, Greece, Belgium, the Netherlands, the USA (continental and Hawaii), Hong Kong, Singapore and Bangkok airport.

Except for a brief trip to Queensland in 2009, I haven’t been out of Western Australia since May, 2009.

Like my father, who spoke three languages with native ease and others he gained from later childhood, I have a great affinity for language. However, along with my native English, I have only French, basic Italian, even more basic German and a smattering of Latin that would be a source of great amusement to any native Roman speaker. (Although my father at times was a translator and interpreter, my Australian-born mother forbade anything but English in the house when we were younger, but encouraged me in my abilities in language and languages later. I’m now catching up to my father fast!)

After attaining my Qualified Teaching Status in England I was offered a further five year contract to teach at my school in England. However, although I enjoyed teaching in Britain and was immensely successful there, due to constantly getting colds and flus, I chose to quit the classroom and on my return to Australia I have lived in Northcliffe, WA, since 2009, during which time I have written fiction, delivered public astronomy talks and completed major research projects in Australian history, the fruits of which are now becoming public, my work in astronomy belayed by the significance of my work in history. I am now also into the final units of my Juris Doctor.

My personal Twitter feed is Joanna Davis@joannatdavis.

While my full name is impressive, I use the abbreviated version, Mum’s name, as a nom-de-plume, merely because it’s easier (unless I ever want to go pro as an opera singer, in which case I will be “Joanna Tatarinova”, a much more fitting name for an opera singer!)

Joanna Davis

(Joanne Tatarynowicz-Davis)